This is really a rare breed… and yet another “cat of prey card” to be flopped: The SPEA Panther.

Basically, it’s an Intergraph Clipper workstation on an ISA-Card. As usual, you can find more details about Intergraph and the Clipper CPU architecture elsewhere.

Most likely built & released 1988, this full-size ISA board features a Clipper C100 CPU(set), 4MB of ram (expandable to 8MB) and quite some glue-logic, mostly buffers, lots of GALs, some DP-RAM – and sad enough: no EPROM.

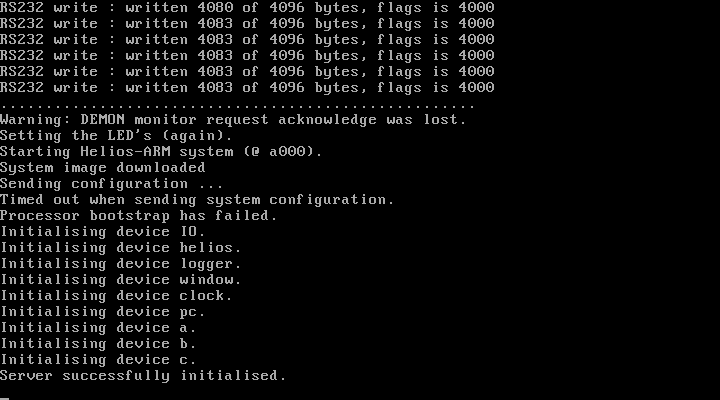

Having no EPROM means it was “booted” by the hosting PC and there’s no clue of how to feed this beast, i.e. what kind of protocol it is talking to the ISA bus.

A german article in the endless archives of “Computer Woche” (21.10.1988) mentions this:

“[…]Für den SPEA-Panther, einem Aufrüstungsboard für PC, steht jetzt die CAD-Software Intergraph Microstation zur Verfügung. Besonderes Merkmal dieser Software ist, daß der Kern unter Unix läuft, die Anwenderschnittstelle jedoch eine DOS-Lösung beinhaltet. Microstation liest und schreibt DOS-Files. Auf Grund der Lösung “Unix under DOS” ist die SPEA-Version von Microstation voll kompatibel zu Workstations.” (Source)

Translated:

“[…]For the SPEA-Panther, a PC expansion card, Intergaph’s CAD-Software Microstation is available now. The particular feature of this software is that its core runs on UNIX while the user-interface is still hosted on DOS. Mircostation reads and writes DOS-Files. Because of the “Unix under DOS” solution the SPEA-version of Microstation is fully compatible to the workstation [version]”

So the Panther was probably running a full version of CLIX, Intergraph’s version of UNIX and the x86-Host was degraded to be the terminal… given the 1988 speed of PCs (Compaq just introduced the DeskPro 386 @ 16MHz), not the worst idea to have.

Well, if it wouldn’t to be the case that the Clipper architecture itself was dying a slow death over the next 2 years…and Autodesks AutoCAD was getting faster as 386/486’s were taking off…

That’s probably the reason why there’s next-to-none info about this card on the web… and print and newsgroups: Too expensive, too specialized, just a hand-full sold.

So just for the fun of it, here are some more detailed pictures of this “one of a kind”. The right half of the card has the ISA bus interface, four chips from Fujitsu marked MB622202 (my guess is it’s Dual Ported RAM), lots of 81C4256 DRAMs (32, so 4MB) and a mysterious gold-lid PGA Fujitsu chip marked C143C1C and 76460… could be anything. Ah, and a dip-switch… most likely for setting the I/O address or IRQ.

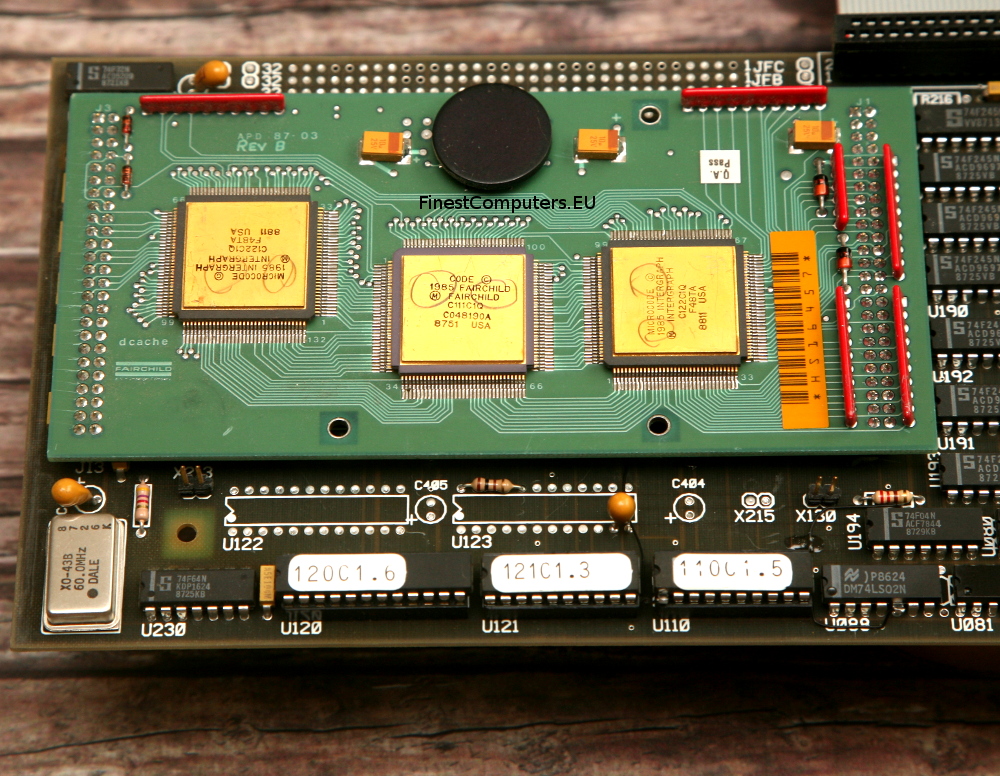

The left side of the card is dominated by the CPU daughter board, obviously provided by Intergraph itself (featuring the companies logo) as I had seen this kind of board before. Above the CPU are even more PAL/GAL chip.

And again, the unknown C143C1C chip, now in its full glory. Next to the chip a 60MHz oscillator which lets me guess that the C100 runs at 30MHz… a bit below standard for C100s.

When buying the card my hope was that there might be more enlightening stuff below the CPU daughter-card. But as most times in life… there was nothing worthwhile 😉

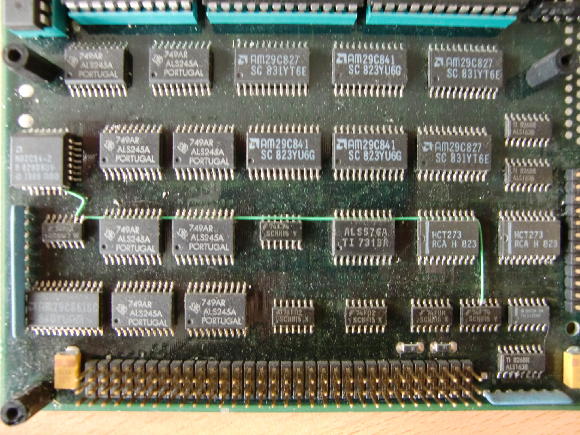

Just lots of TTL logic and buffers… the PLCC on the left is a N82C54… a CHMOS programmable interval timer… boring.

So to conclude this chapter, I guess I won’t make this card run again – ever. It’s just another example of how undecided the computing world was around 1988. There where more than one way to reach your target (speed) but most of them failed. Still I think it was much cooler than today.

Update 2016:

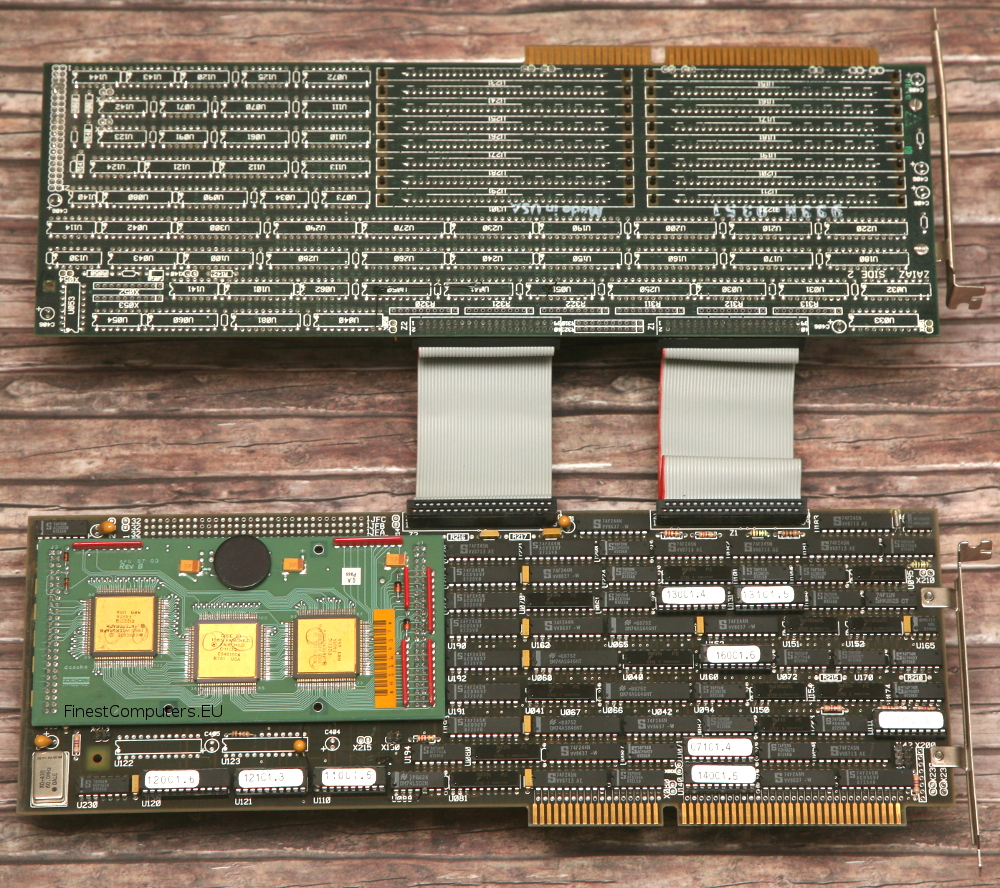

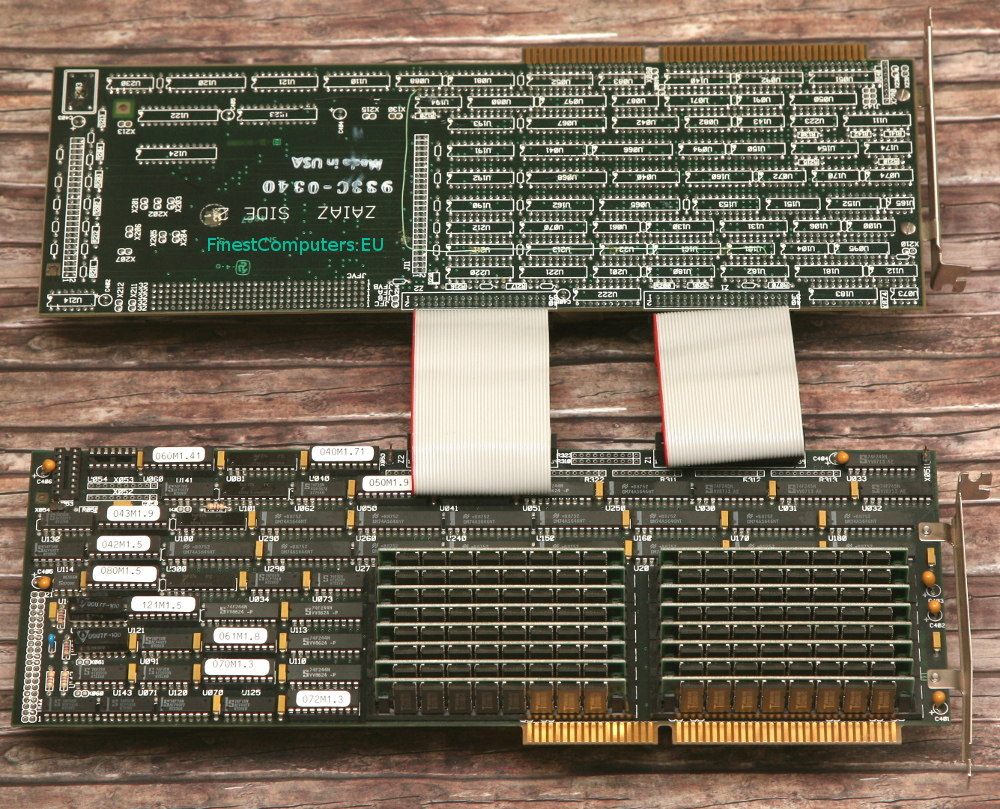

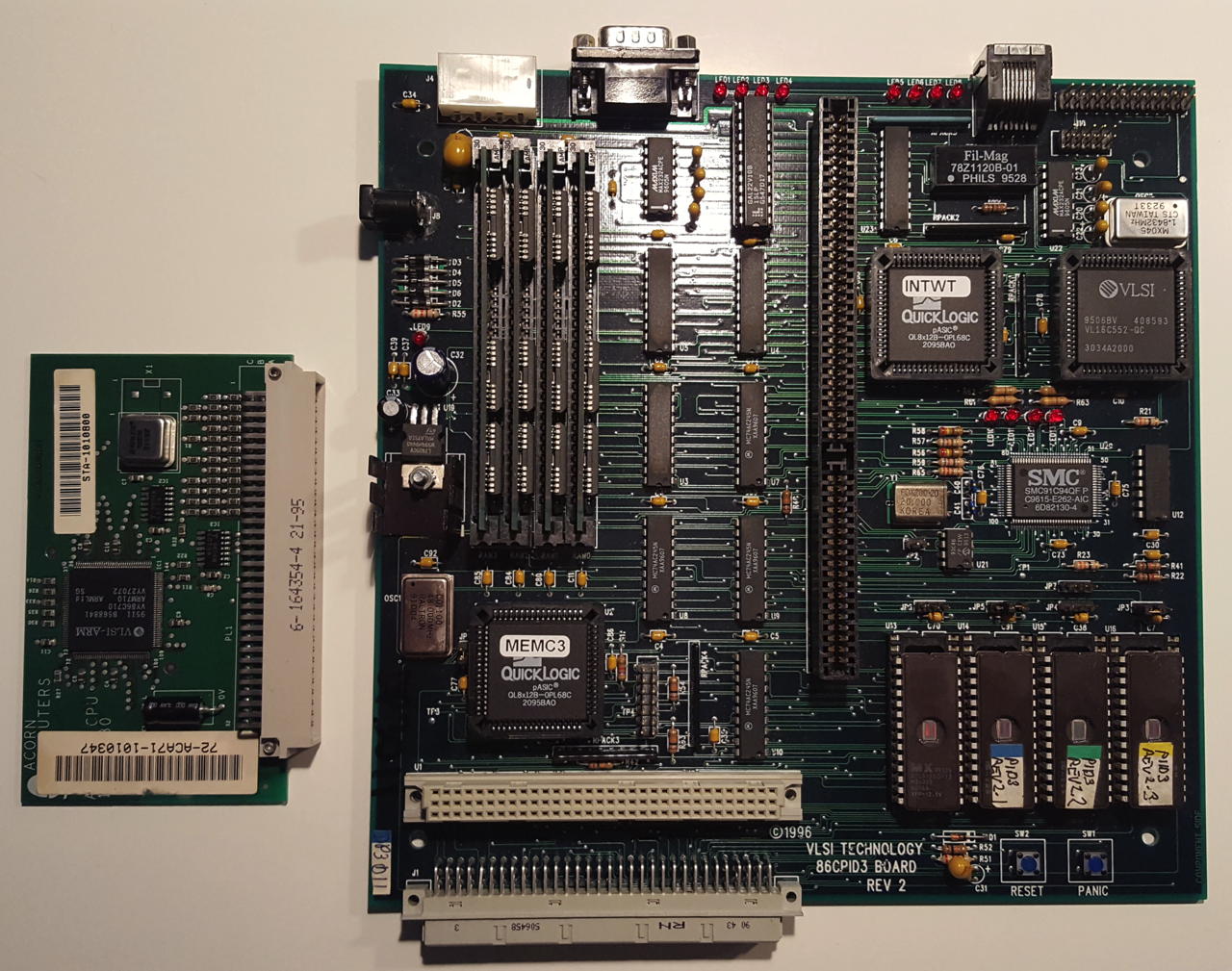

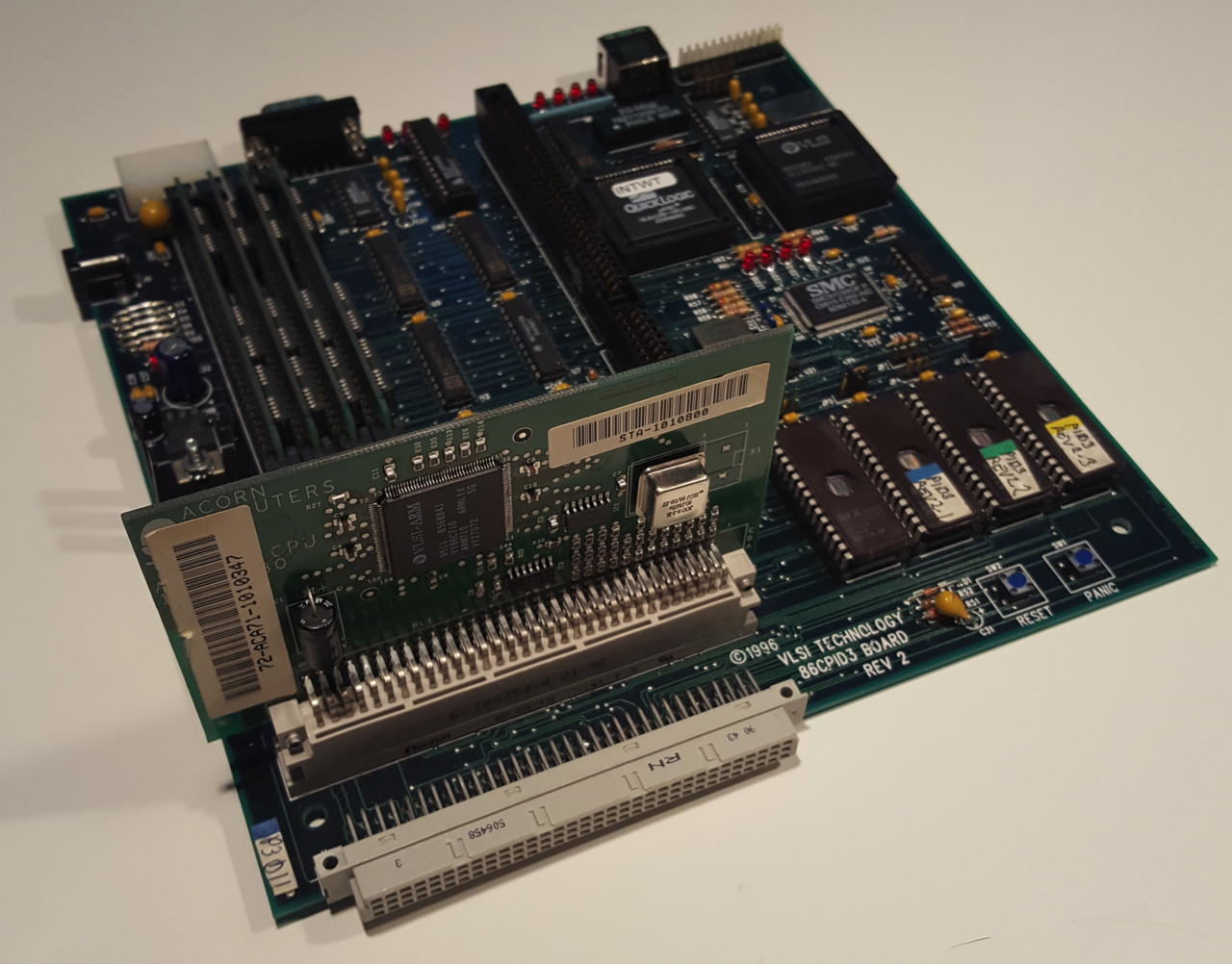

Found an interesting auction on ePay… this is the original Clipper card – which seems to be the “blueprint” for the Panther… SPEA just replaced the tons of discrete logic by some ASIC chips, which made room for RAM. On the original cards that is placed on a separate daughter-card:

(Pictures courtesy of FinestComputers.eu)

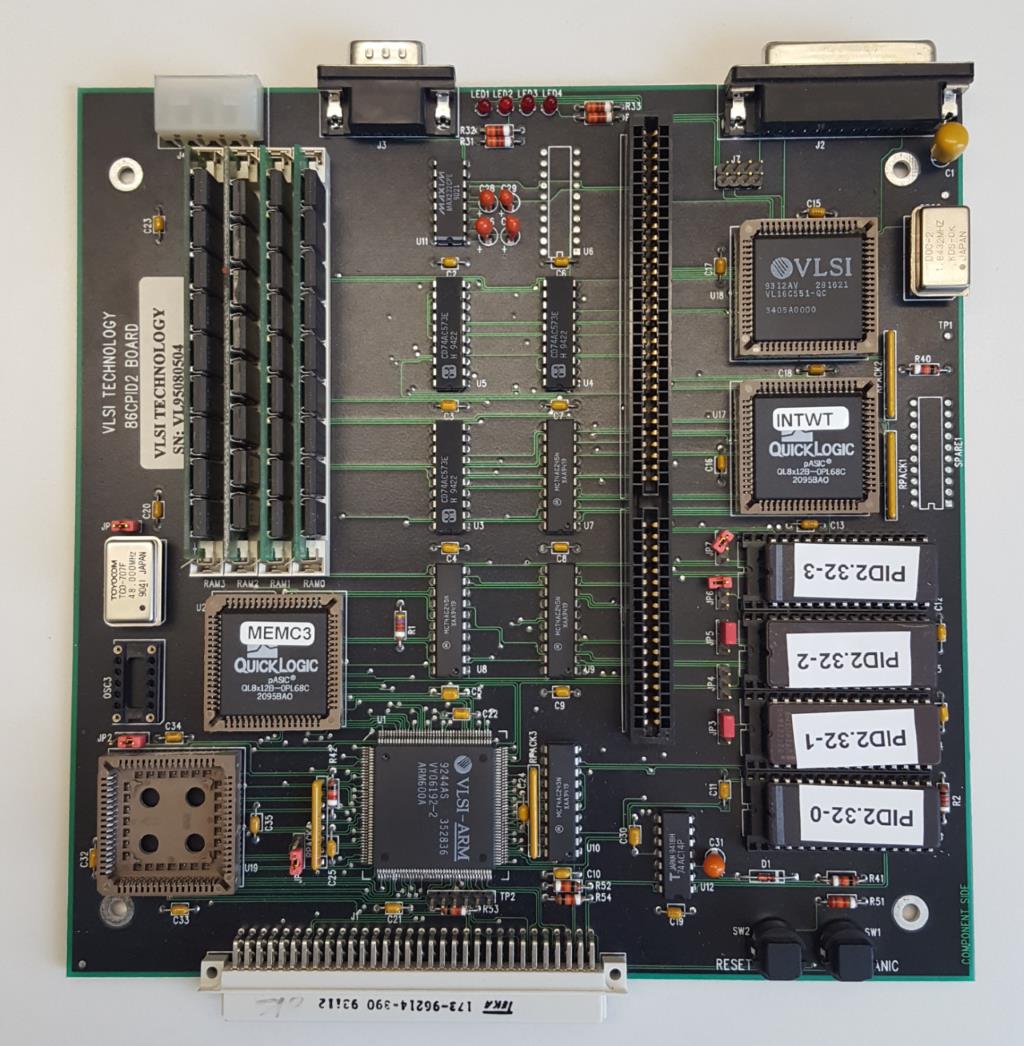

The CPU card back side and RAM card front:

The CPU Module is the same as used by SPEA: